The Whithorn Trust Blog December 2021

Blog 4: The Iron Age Roundhouses of Black Loch and Whithorn

The Iron Age Roundhouse at Whithorn is based on remains dating to 2500 years ago. These remains however were not found at Whithorn itself, instead they were found at a place called the Black loch of Myrton 5 miles to the west of Whithorn, between Port William and Monreith, in 2013. The remains found there were startling, preserved in peat bog, constantly wet and boggy ground. These were found to be the remains of “Roundhouses” including an amazing series of wooden woven floor panels and the intact lower portions of internal posts preserved beautifully in the bog. Through “Dendrochronology”, measuring the tree rings in the preserved wood, The Roundhouse (which the Whithorn Roundhouse is based on) was dated to around 435-450BC, early in the period known as the Iron Age. This Roundhouse, which stood alongside two other Roundhouses dating to around 435-450BC and near two others dating to 200BC, is an extraordinary survival from a period when Scotland did not even exist.

At Whithorn however, during the 1980s Dig under Peter Hill, there were the ephemeral remains of Roundhouses found towards the end of the Dig in the area of the “Glebe Field” downhill from the ruins of Whithorn Priory. Sadly, these remains, found in the south portion of the field, were much less well preserved because the conditions were more typical of most archaeological sites, relatively permeable dry ground and the fact that these Roundhouses were found in the deepest layers of the site, where evidence is often but not always more “ephemeral” than upper layers. These Roundhouses will be explored alongside those Black Loch Roundhouses as a point of comparison. To make clear and to bear in mind, the Roundhouses at Whithorn should not been seen as “worse” versions of the Black Loch Roundhouses, rather the Black Loch Roundhouses should be seen as something like archaeological “Gold Dust” because of how well they were preserved.

The Iron Age is a period which is longer and shorter depending on which areas (which we can carefully talk about in relation to modern countries) we are talking about. While many will know that the Iron Age in England and Wales stretches from around 800BC to 43AD, ending with the invasions of the Roman Empire, in Scotland, things are more complicated. In the area now known as Scotland, Scottish archaeologists argue that the “Scottish” Iron Age lasted from 800BC to possibly as late as 800AD. In short, this is because while there are certainly Roman remains in Scotland, they are almost entirely of a military nature and the nature of the interactions with native people is still much debated. Certainly, if you were not a Roman Legionary, you were probably living in a Roundhouse, much as you had been before. To be clear however, the length of the Iron Age means that Roman-Native interaction makes up only about a quarter of the “Scottish Iron Age.” No one at the Black Loch of Myrton settlement at 450AD was in the regular vicinity of a Roman legionary. Indeed, the Roman “Republic” was still in the process of conquering Italy at the time. In comparison possible dating for the Whithorn Roundhouses could put them between 1-500AD, about five hundred to one thousand years later! In this time frame, the inhabitants of these Roundhouses at Whithorn could and probably did interact with Roman legionaries who had invaded what is now Scotland with the Roman Army of the now Roman “Empire” from about 80AD.

The major issue with the Iron Age in Scotland, especially in 450BC, is the lack of written sources. It seems that Iron Age people relied on word of mouth or “Oral Tradition” to pass down knowledge, there is no evidence of native writing for the vast majority of the Iron Age. What written sources we do have, are written by later outsiders, mainly Romans and therefore should be read with caution. They looked at the area of Scotland from an invader’s point of view and we effectively we cannot be sure how well their impressions matched up with native society as it was. A map based on the geographical research of Ptolemy, a Greek Scholar in the Roman Empire, of the British Isles dates to around 120-150AD. It says that in the area now known as Galloway, there was a tribe called the “Novantae.” We cannot be sure however that the Novantae existed 600 years beforehand, in 450BC. It very well could be that Iron Age Galloway was a series of effectively independent small settlements. A further issue is that while we do have high status objects found in Galloway dating to the Iron Age, they don’t seem to correspond to settlement sites. High status objects and evidence of their making on settlement sites would be archaeological evidence of a high-status settlement for a powerful chief. Normally, they tend to be found in burials or as “depositions” or offerings at a ritual site. For example, the “Torrs Pony Cap” found at Torrs Farm near Castle Douglas was discovered in a peat bog in the early 19th century. It is an amazing helmet for a horse made of bronze and found associated with the two bronze horns found with it (most likely attached to the helmet, dating to around 300BC. Archaeologists argue that while some weaponry has been found in Galloway dating to the Iron Age, such as broken sword blades in a bronze cauldron at Carlingwark, Castle Douglas, this probably represents small bands of warriors who were probably more like raiders rather than soldiers in armies.

The Roundhouse at the Black Loch of Myrton, reconstructed at Whithorn in 2016/7, however, had no evidence of weaponry or finished high status goods within or around it nor any of the other Roundhouses, apart from moulds or crucibles for bronze casting in the 200BC Roundhouses. A Roundhouse is a circular building which would mostly but not always made of wood normally with the fireplace or “hearth” in the middle of the building, normally surrounded by rings of upright wooden posts holding up the roof. Normally wood would not survive on an Iron Age site as most sites are on dry but permeable ground, so would rots away. Most are only identified through “post-holes”, the circular pits in which upright posts would be set, in order to hold up the roof.

At Black Loch, things were different, the peat bog resulted in the amazing survival of the wood on the floor. It is the survival of this otherwise mundane aspect of Iron Age life that is so extraordinary. This allowed the archaeologists from AOC Archaeology to uncover a very substantially built Roundhouse with an amazingly well-preserved wickerwork floor as well as a substantial stone and clay hearth. The wickerwork floor had plant litter placed on top, including water reed (a possible roofing material) up to around 0.5m(around 20 inches) deep below ground level. This also included the preserved foundations for two concentric “rings” of internal wooden posts (each around 30cm in diameter) inside, which would have held up the roof as well as the foundations for a” double” wicker wall, making this Roundhouse 13.2 metres in diameter. This does not include the magnificent entrance with two flanking radial oak logs 2.2m long with tangential logs between them. The radial logs had three substantial mortice slots carved into each log for substantial doorposts. Even more remarkable, is that dating of some of the internal wooden posts suggests that planning of the structure and stockpiling of this wood for that purpose may have started as early as between a year and 18 months before final construction! The other Roundhouses were similarly well preserved. The main differences were that that the three Roundhouses dating to around 450BC, including the one above measured around 13m in diameter each, whereas the two later Roundhouses (around 200BC) were smaller at around 9-11m in diameter. Above ground-level, the Roundhouses survived up to about 0.25m(about ten inches) from the ground, which may not sound like much, but up to ten inches of wood is normally ten inches more than is normally found on Iron Age sites. On most sites you find no surviving wood at all.

Indeed, in was in these “normal” conditions that Roundhouses were found in the Glebe Field at Whithorn during the 1980s Dig by Archaeologist Peter Hill and his team. They found, as they described “ …a settlement of insubstantial Roundhouses…”. Digging deeper into the reports, there was one of those Roundhouses which seemed to be the most distinct. Even here, there was none of the beautifully preserved organic wood that would be found at Black Loch. The remains, called “Structure 11”, which at most extended to around 6.5m in diameter (around half the size of the early Black Loch Roundhouses) consisted of a “shallow groove” on its eastern side, possibly a wall foundation and an “irregular arc” of postholes in the southwest portion. This evidence as noted by the Whithorn archaeologists, was insubstantial, with no real evidence of door posts or any evidence or internal posts, as there was at Black Loch. The only possible dating evidence for this structure is a scattering of nine or so pieces Roman Samian Ware pottery and Roman glass, including pottery from Gaul (modern France) just around the outside of the structure. Peter Hill, Dave Pollock and Jo Moran thought this could potentially date this probable Roundhouse to around 100-300AD (Roundhouses have been found in Scotland dating to as late as 700-800AD), but this was not certain, due to the complexity of the archaeological layers or “stratigraphy” of the site. In other words, the glass and pottery may not be associated directly with this Roundhouse, it could for example have been discarded by people after the Roundhouse fell into ruin. Sadly, the evidence for the other possible Roundhouses were even less substantial than that. Among the other possible remains included a “deep curvilinear ditch” which clipped the east end of structure 11, continuing south-east as a possible wall foundation, with a piece of antler and a lump of haematite iron ore found in it. There was a sub-rectangular “Building 12” with south and west “stake lines” towards what might have been the middle of this Roundhouse, maybe some of variation on an internal ring of posts, or more likely a “successor” building built afterwards. There are also a series of drains running northeast to southwest from the aforementioned “curvilinear ditch”, which may represent another possible Roundhouses. There was also “Building 14” to the north-east of structure 11 represented by a north facing semi-circular “shallow rock-cut gully” with a “pair of post sockets” possibly representing a doorway and a “truncated floor surface” but no finds. There was some charcoal found in the area of these possible Roundhouses but that has not been able to be dated with radiocarbon dating.

As can be shown, this is tantalising evidence of possible or probable Roundhouses at Whithorn but as with most archaeological sites, dating these structures is much more difficult if you do not find organic remains like wood which you can date through dendrochronology like at Black Loch or other materials like datable charcoal through radiocarbon dating. In other words, the key difference is not that the Roundhouses at Whithorn have poor dating evidence, it’s more that the evidence at Black Loch is so exceptional. This is probably why, in the “Whithorn Dig” Booklet, with photographs and illustrations, published in May 1991, towards the end of the Dig, summed this up, by saying that, “…There was a settlement of insubstantial roundhouses at the foot of the Slope(in the Glebe Field) until about 500AD…” In other words, these Roundhouses probably date to what is called the “Late Scottish Iron Age” between 1AD-800AD(though this overlaps with the early medieval period in Scotland, which many scholars date from around 500AD until 1100AD in Scotland) but we cannot be more precise, other than to say that Structure 11 probably was constructed between 100-300AD.

This is frustrating because better dated evidence would give us a clearer view of the earliest phases of Whithorn. We know that there is more securely dated evidence for the period between 500-700AD at Whithorn , with huge quantities of pottery. Whereas we might have some twenty or so pieces of Roman glass and pottery from between 100-300AD, from around 500AD to 700AD, it is in the thousands, with about 431 pieces (or sherds) of glass (originally intact high status cups, beakers and even bowls) alone from France and the Mediterranean. As the archaeologists said at the time, Whithorn must have been an important place to be able to import such pottery such as amphora containing wine and olive oil. Some of this pottery is very well made and high status, the sherds of “African Red Slipware”, originally bowls and plates, for example was made in late and post Roman North Africa, particularly Tunisia. This is the pottery a wealthy merchant or landowner in the post Roman world would bring out for banquets. Therefore, it stands to reason that the trade links that brought such vast amounts of high-status goods must have been set up at some point before 500AD. In addition, there are substantial burials in the form of Log Coffin and Long Cist burials in the area north of these Roundhouses that have now been radiocarbon dated by the Whithorn Cold Case Project but only as early as around 600AD-800AD and are far enough away to make associating Roundhouses and burials debatable. There is also the famed “Latinus Stone”, the earliest Christian Monument, in Scotland dating to 450AD with an inscription in Latin. Found outside the Dig Field on the Priory Hill, it shows, like the pottery, wide ranging connections and adoption of aspects of a Christian Latin speaking possibly late Roman culture by “Latinus” and his daughter (No name sadly), who were most probably part of a native aristocracy. The problem is that any possibilities of Latinus, his daughter or their ancestors living in one of those Roundhouses with the possibly associated 100-300AD Roman pottery and glass, is hampered by the lack of precise dating evidence. Finding better dated material with the Whithorn Roundhouses could have helped us answer these questions; it is frustrating that these Roundhouses could have done for Whithorn what Black Loch has done for the early Iron Age in the area. In other words, it would have really helped tie things together.

In sum, this shows the real variation in the kinds of evidence we have for the Iron Age in Scotland and in the particular the area around Whithorn. This has been shown through the variation in the way that the remains of the Roundhouses have been found. With Black Loch of Myrton we have clear indications of a populated and thriving area with sophisticated skills and knowledge for building monumental structures as the heart of the community. On the other we have evidence for Whithorn as a centre of long-distance trade from 500AD but not enough evidence to say with certainty that the probable Roundhouses at Whithorn were part of the origins of those trade networks in the late Scottish Iron Age. What is for certain however, is that research and scholarship will keep back to these questions and maybe one day, we might get more of an answer about what this all means.

Whithorn Trust Blog 3 2021

The Viking Age Wicker-Wattle Houses

There are the remains of grand Church buildings built at Whithorn, but also the remains for much more mundane buildings. These mundane building can be just as fascinating as the more high status buildings like churches. They can tell us about how more ordinary people lived and worked in the past.

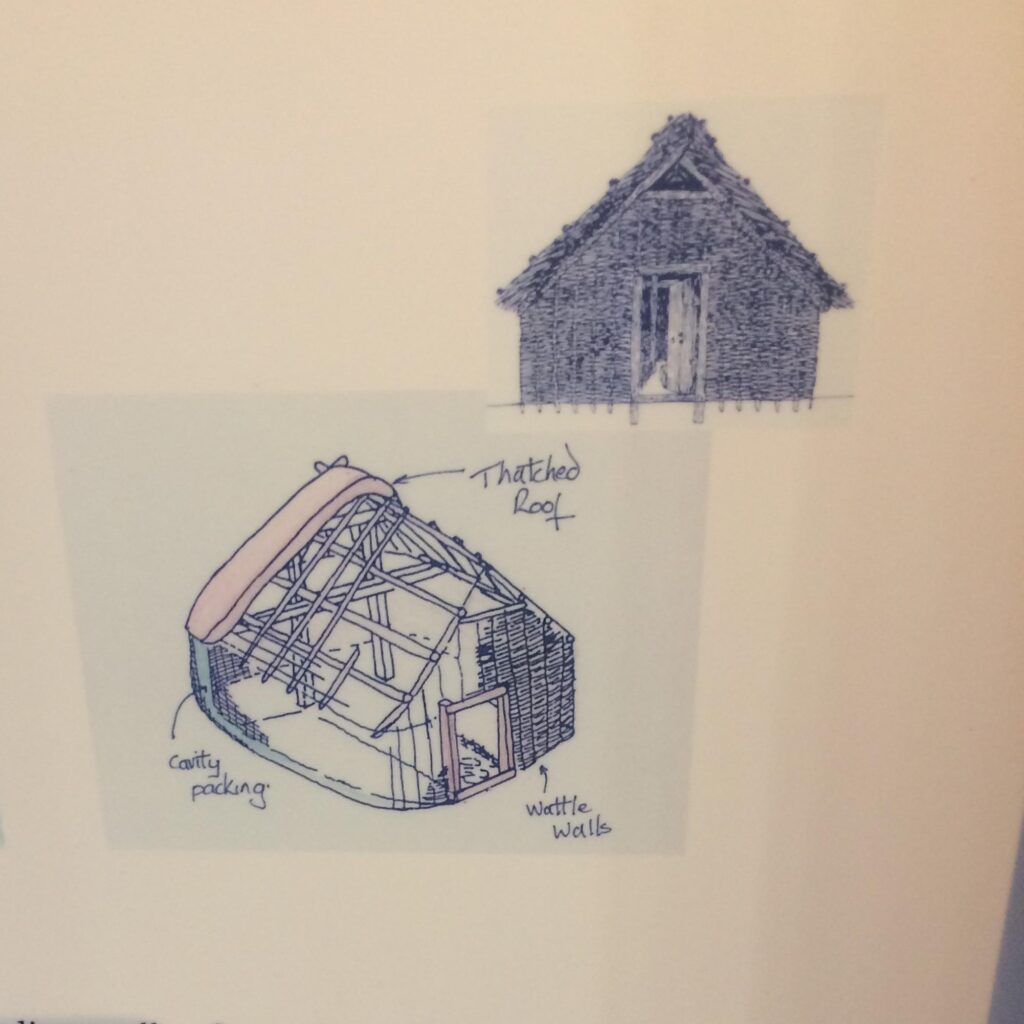

The Viking Age Wattle Houses are such an example of how ordinary people lived during the “Viking Age” at Whithorn. These wattle built “box” buildings seem to show great change in the area of the “Glebe Field” where they were found as part of the 1980s Dig at Whithorn. From around 900AD, when these houses were built, Whithorn seems to have gone through a transformation from 800AD into 900AD.

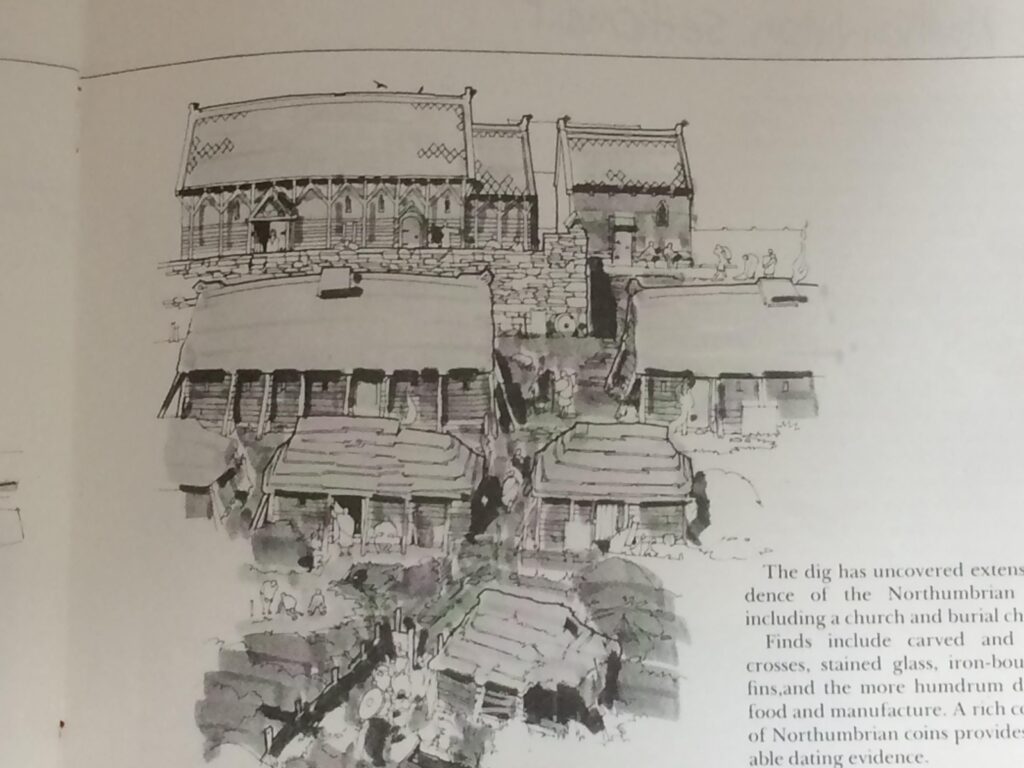

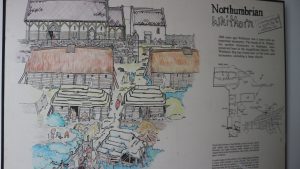

The archaeology of the Glebe Field found in the 1980s, seems to show a marked shift from ecclesiastical use in around 800AD. Around 650-700AD, the Northumbrians(of the kingdom of Northumbria centred in now northern England) had conquered the area and had set up what looks like part of a monastic precinct in the form of the Wooden Northumbrian Church, Clay Burial Chapel and Feasting Halls. By 900AD it was much different.

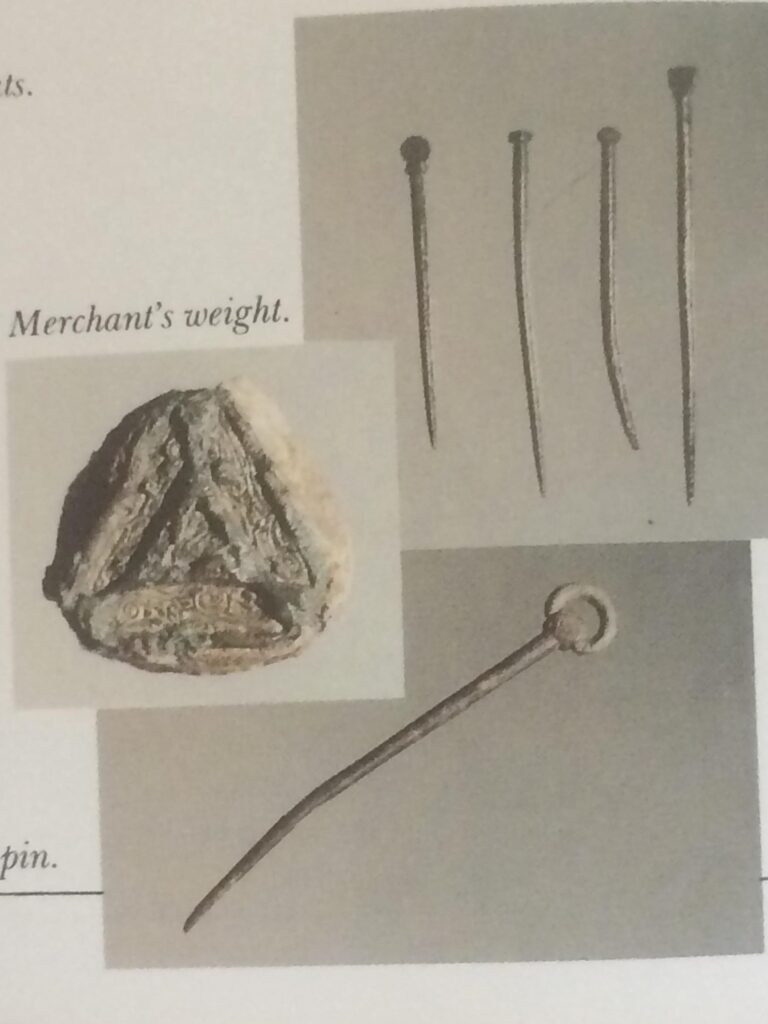

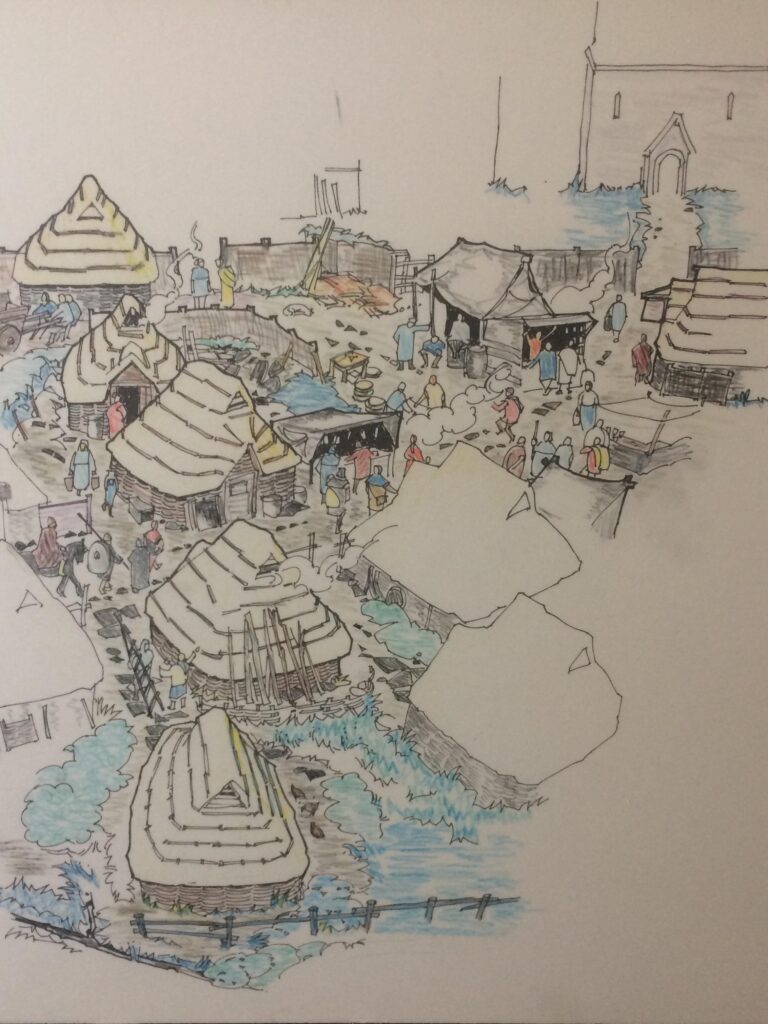

In 900AD, the area had shifted in use to become an extensive market. Gone were the signs of monastic life in this area, instead there was evidence of intensive activity associated with a more secular mode of life. In amongst the about forty- eighty wattle built houses found on site, evidence was found that many of their occupants had been traders and craftsmen. The evidence of crafts were some of the most extensive. There was evidence for leatherworking including the amazing survival of a sole of a leather shoe as well as offcuts showing that they were being made in the area of the Glebe Field. There was also evidence of antler working for the making of items like riveted combs. What might be surprising for some, is the huge amount of flint found, used most likely not just as firelighters but also for working with animal skin and other materials. More disturbing to our modern sensibilities is the number of cat bones which attests to use of cat fur for lining and trimmings in clothing. There was also evidence for metalworking with lead and copper working as well as gold and silver. There were also merchants’ weights and thistle headed pins as well as loom weights and spindle whorls showing weaving. The distinctive head of the pins seemed to show huge similarities to pins found in Dublin from the same time period. Indeed the evidence for a market area in Whithorn has striking similarities to the archaeology of early Dublin at the same period where Vikings established a settlement which became a town and major trading centre. It appears that these Vikings adopted the Gaelic language from the native Irish and so their culture has become known as the Hiberno-Norse. Indeed the evidence suggests that Whithorn was part of a trading area that encompassed the area of the Irish Sea and the Western Isles of Scotland including the Hebrides. Was this a settlement of Vikings from Ireland, the “Hiberno-Norse”?

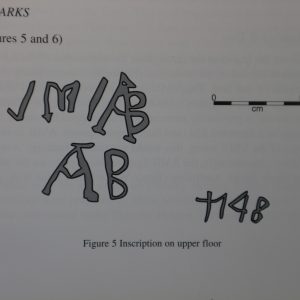

Some scholars and archaeologists thought so as there was signs of a fire in the area of the Wooden Church and Burial Chapel. This was taken by many as definite evidence of a Viking attack which killed or chased away the previous population, leading the shift in the use of the Glebe Field. There is even the argument that could have been Scots with the warlord Alpin claimed to have been raiding Galloway before dying in 841AD. However, the fire did not extend into the area of the Feasting Halls and evidence for rebuilding of the Wooden Church has been found. The fire may have therefore been an accident but indeed even if it was a Viking raid, it appears that it did not involve wholesale replacement of population. Indeed, three inscriptions on Stone Monuments known as “Whithorn School” Monuments dating to between 800-1000AD, have been found to be Anglo-Saxon Runes not Norse. It shows that there were people, and with the wealth to commission these Monuments who still spoke Anglo-Saxon at Whithorn.

Therefore the occupants of these houses would have heard not only Norse or Gaelic spoken but also Anglo-Saxon as well as possibly speakers of Old Welsh or “Cumbric”, as the marketplace thronged with people.

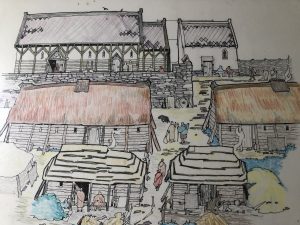

The Houses themselves, many of which doubled as workshops, had walls made from wicker. The wicker or “wattle” would have been made from branches from trees like hazel or willow, woven together to make wooden screens. These were then erected as walls, sometimes sunk into the ground in small trenches or “gullies”. There does seem to be some evidence for “daub”, mud and other materials used to “pack in” the wicker to fill in the gaps and make it a solid wall. The walls formed a “sub-square” or box shape with rounded corners because of the shape of the wicker. Post holes show that upright posts would have held up the roof, which the archaeologists argued would be a double layer of wicker screens and thatch. The thatch might have been something like water reed or other materials such as straw. The entryways seemed to have had stone paving going to a small square hearths, filled with clay and lined with stone slabs. Some of the houses had evidence of comb making and weaving around them and sometimes just outside the doorways.

Interestingly, these were not the first type of wicker work building. There were earlier buildings dating to around 850AD which were wicker built but “sub-rectangular” with doorways in the narrower walls. This was at a time when change was already afoot, as the Wooden Church shows signs of conversion into a barn with signs of what may be contemporaneous ploughing outside. There were even some of these wicker work rectangular buildings with evidence of craftwork like the later square buildings including waste from antler-working and metalworking debris. This certainly suggests, with the other evidence for some continuity, that the “secularisation” of this area may be due to shifting “land use”, the monastic site refocussing elsewhere and continuing (possibly to the Priory Hill), rather than destruction and replacement by conquest.

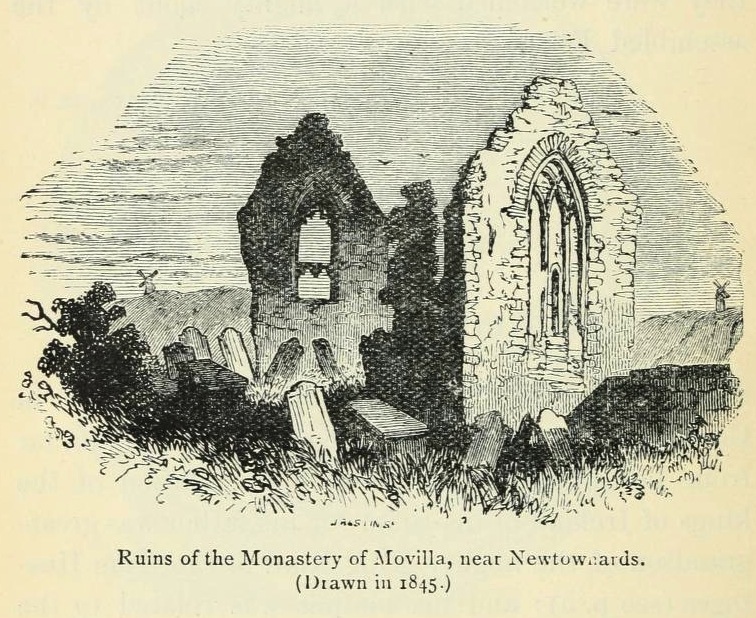

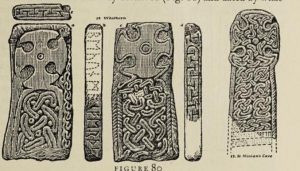

Indeed, there is some evidence for a continuing monastery. Stone monuments in the form of disc shaped crosses were being made in the area of Whithorn. They have found in various areas around Whithorn and the Machars. The greatest concentration however have been found at Whithorn, found reused in the later Medieval Priory remains, reused as building stone and found in houses in Whithorn, as well as in the 1980s excavations. These Monuments are called the Whithorn School Crosses because of their distinctive “Disk” Shaped head (with a figurative stylised cross carved onto it) and the looping “Celtic” interlace down the shaft of the cross. These Monuments date to between roughly 800-1000AD and because of the quantity of these Monuments at Whithorn, it is argued that it is most likely at Whithorn that carvers and sculptors made these monuments. With intricate designs inspired partly by monastic manuscripts, their workshops would most likely be part of the monastery. The area which the other monuments of this kind have been found, encompasses the Machars Peninsula, normally in areas associated with a Church or cemetery. These monuments indeed may have served as a place for services before a Church was present in addition to grave markers. It has been argued that this may show the influence of a continuing monastery at Whithorn. The best example is the “Monreith Cross” originally erected on the “Court Hill” at Monreith, which dates to around 900-1000AD. There was no evidence of a Church or cemetery nearby, so it argued that the Monreith Cross may have been erected by a local lord, possibly to show his piety and make a place for services. Furthermore, there were implements found that suggested manuscript making consistent with a monastery. There were “Styli” such as bronze “Stylus”( like a metal quill) used in “pricking” and writing on manuscripts most probably made of “Vellum” basically made of animal skin (which did not survive). While some of the implements may be from 1300AD onward, two were thought to date earlier to around 1000AD, the date of the Viking Age settlement.

Therefore, it may have been that as the coppersmith, antler carver or weaver set to work on their craft inside or beside their dwelling, there may have been the monastery on the hill itself. Maybe a monk or nun came down to buy something for the monastery or themselves, accidentally dropping a stylus as they went ( or maybe the writing Hall or “scriptorium” was nearby).They might have seen the workshops where carvers were carving the great slabs of “greywacke” stone into magnificent monuments now known as the Whithorn School Monuments. There would have been the sounds of weaving and metalwork as the marketplace hummed with activity. In all of this stood, these Wicker Wattle Buildings, homes and workshops of ordinary craftspeople and merchants, not grand buildings like a manse or a church but fascinating nonetheless.

Whithorn Trust Blog 2021

Blog 2: The Northumbrian Church

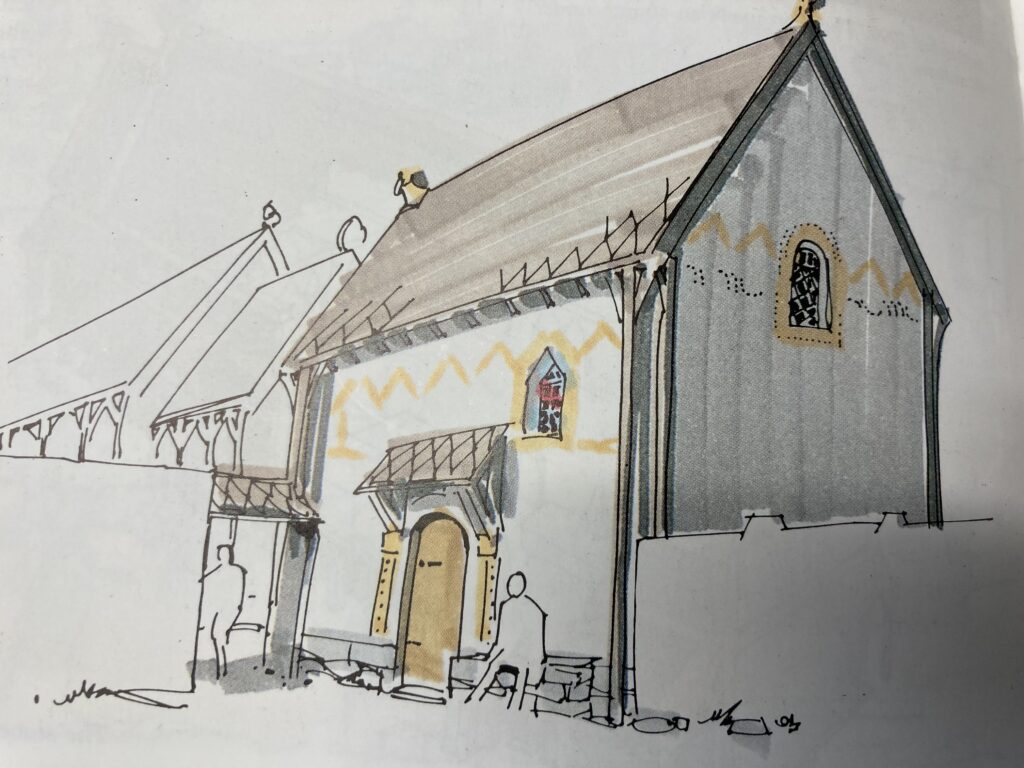

The Northumbrian Church, found in the Glebe Field, is the earliest archaeological evidence of a church yet found at Whithorn. The Whithorn ReBuild Project is currently examining the structure of the Northumbrian Church that was found in the Glebe Field at Whithorn in 1990 as part of the Archaeological Dig lead by Peter Hill between 1984 and 1991.

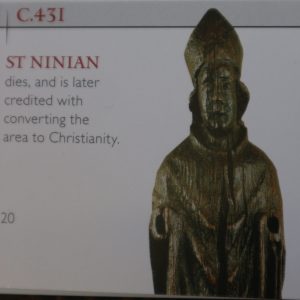

The remains were dated to around 700AD, the period when the “Northumbrians” from the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of Northumbria had taken over in what is now Dumfries and Galloway. The Church appears to have stood in a monastic precinct as part of a monastery of Whithorn attested by the monk Bede. With Bede writing in 731AD, this is the first documentary evidence for Whithorn and a monastery there. While Bede and later writers state that there was an earlier Church and monastery founded by a holy man and Bishop known as St Ninian, between 397 and 431AD and called Candida Casa (White House), no confirmed evidence has been found for this earlier church.

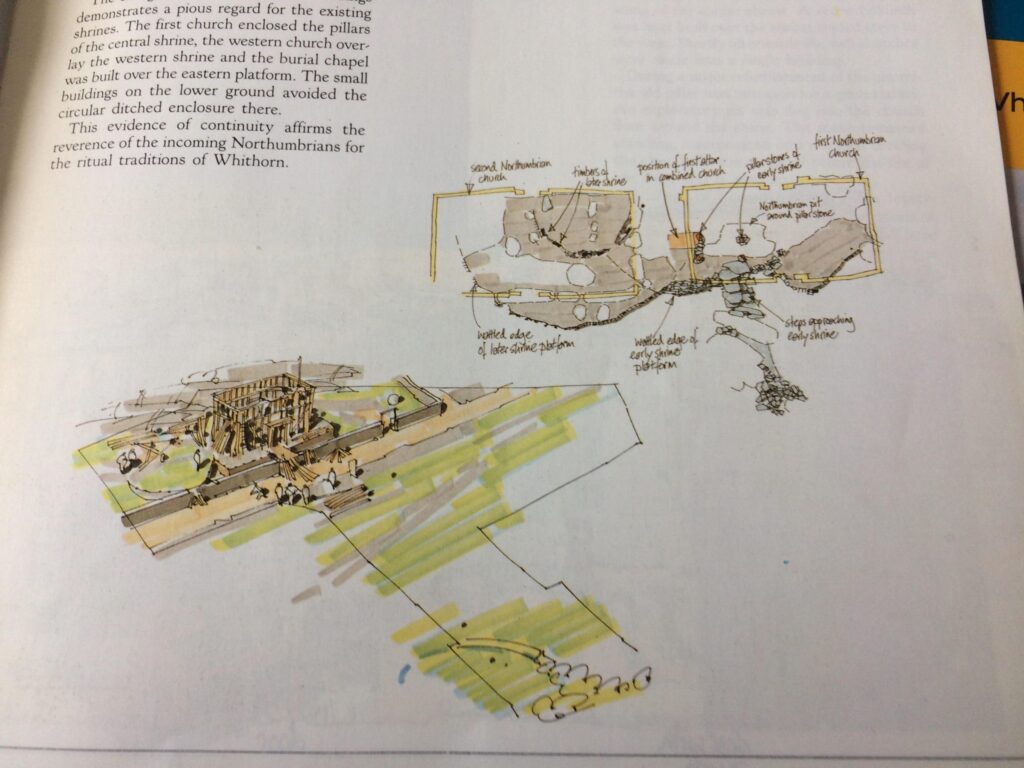

Therefore, this Northumbrian church is the earliest known, archaeologically speaking, on site at Whithorn. At around 700AD, this is one of the earliest excavated churches in Scotland. However it was not the first structure found in this part of the Glebe Field. During the 1980s Dig, the archaeologists found what were interpreted as “Shrines”, circular platforms, some with rings of “post holes” which seemed to have held upright posts. Some of these were found underneath the site of the Northumbrian Church. These seem to have been then incorporated deliberately into the church, possibly with some reverence for those previous traditions. These have been interpreted as Christian shrines for the early Christian community at Whithorn around 450AD. This community is attested by evidence found in the Glebe Field of a wealthy community, high status pottery and glassware from Gaul (modern France) and the Mediterranean as well as high status metalworking of gold and silver. There is even evidence of advanced plough technology and a millstone from a possible mill. Furthermore, as this community developed, radiocarbon dating from the Cold Case Whithorn Project has shown that from around 600AD burials in log coffins and long cists (coffins made of stone slabs) were laid out. Crucially some of these burials have had their human remains dated to around 800AD (into the later Northumbrian period), so we know that with a continuity of burial practices as well as from isotope analysis that there was a sizable local population at Whithorn through the early Christian and Northumbrian period. Therefore, the Northumbrian Church was being built in an evolving rather than a new settlement. In other words, the Northumbrians were interacting with a sizable local population rather than replacing them

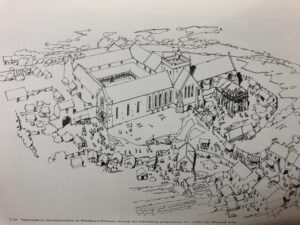

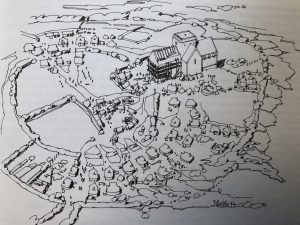

The evidence from the 1980s excavations showed that this Church was within a monastic complex which may have extended up the hill where the much later Priory Ruins stand today. There may have been a bigger Church underneath the Priory ruins, with the “Northumbrian Church”, representing a secondary church. However, excavations in the 1940s by archaeologist Ralegh Radford on the Priory Hill found indications that any remains under the Priory ruins had been levelled before Whithorn Priory in stone was built in around 1100AD.

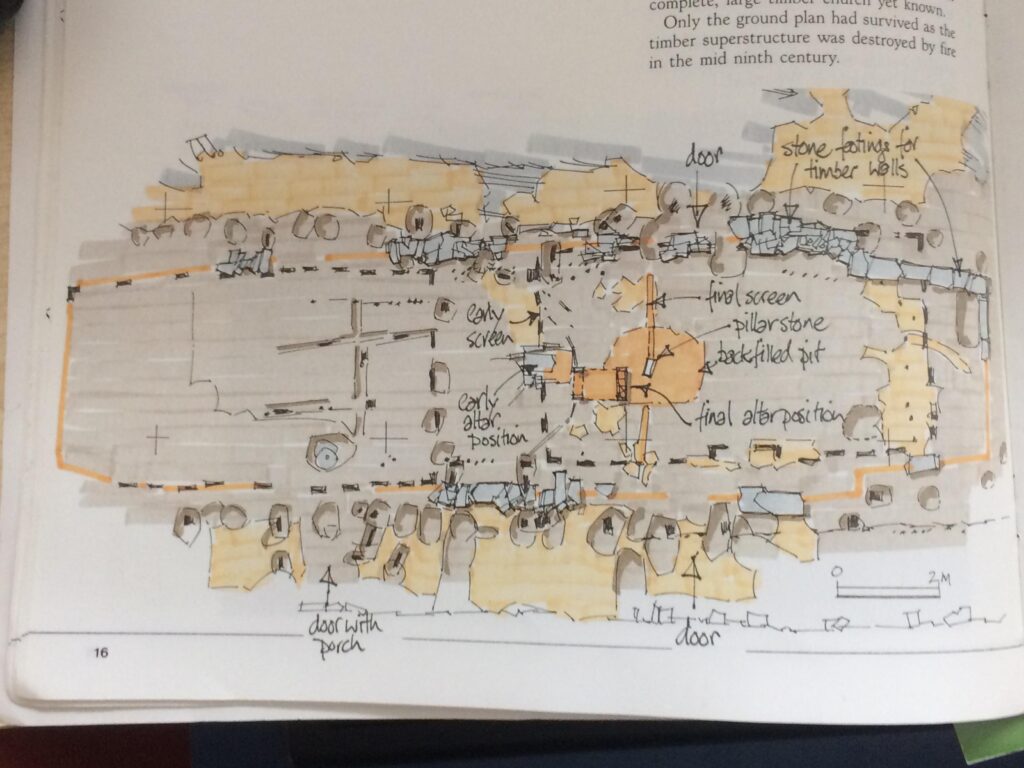

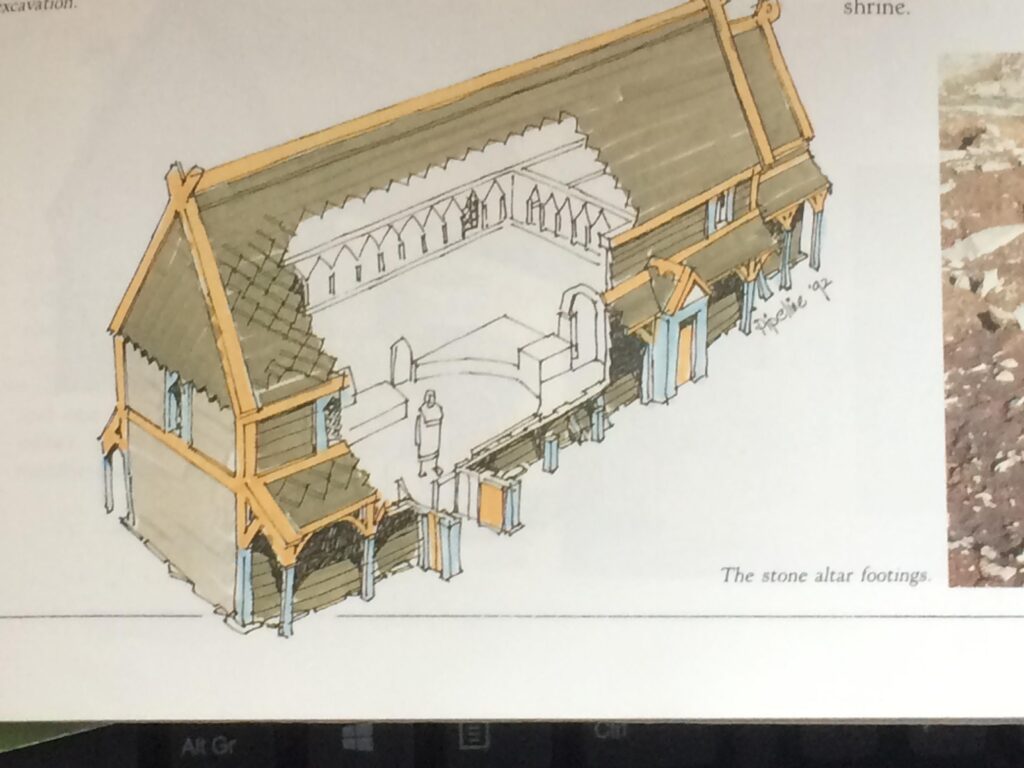

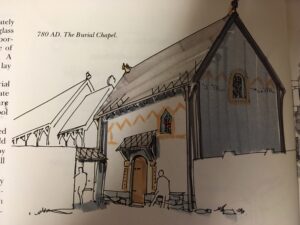

It appears that the Northumbrian Church started as a smaller building for prayer called an “Oratory” which appears to have been built around a stone monument, possibly part of the earlier shrines. This Oratory was 7.5m in length and 4.5m in width. Then, a second western Oratory was built beside it, 8.2m by 4.5m. Around 735 AD, these buildings were joined into a single building, the Northumbrian Church, which was 17.9m long and 4.5m wide. Around the wooden Northumbrian Church, there were other buildings including a Burial Chapel with clay walls and evidence of stained glass windows with four coffins inside with iron fittings. There were also “Feasting Halls”, timber buildings which had evidence of high status feasting that included goose and mutton. There was also the area in front of the Burial Chapel which was a childrens graveyard.

This Northumbrian Church was excavated extensively during the 1980s excavations with the archaeologists finding evidence for an extensive floorplan. This floorplan included evidence for a two lines of posts outside the main structure north and south, which seems to have been covered porches or “arcades” on the southern and northern part of the building, suggesting this Church was quite high status. Inside the building, there was evidence for stone footings for the timber walls and evidence that there was once a screen, probably made of wood that separated the building into two parts. The western part was the “Nave” and the eastern part would have been the “chancel”. The Nave was the entrance where religious services would have taken place with an altar for the monk or priest on the western part of the screen. There was no evidence of dedicated seating in this area. Near the altar were found objects including a roman pottery sherd from central Gaul, now France (dating from the period of Emperor Antonine 138-161 AD) as well as a Roman coin (Emperor Constans 337-350AD). Whether these are offerings by pilgrims at the altar or some other reason is unknown. The “Chancel” was inner sanctum of the Church where the monks would keep sacred vessels and vestments. Later finds including small jumbled paving stones, suggest areas with raised paved stone flooring inside the church which ties up with evidence found for outside paving as well. An extension of the East End (Chancel) around 760AD included a clay and then wooden floor and external posts on the corners (possibly similar to the arcades). The monumental stone mentioned earlier seems to have been incorporated into the screen, so it was clearly important. The stone has been lost as it appears to have taken out around 840AD. However this does seem to show, with the incorporation of the stone and the earlier shrines within the Church, a co-opting of these previous features on site. The Church has not cut across the features but seems to be built with respect for them.

The Church appears to have continued in use until around 840AD when a fire heavily damaged both that building and the Burial Chapel. While some have argued that this was caused by Viking attack, it may have been an accident. There does seem to be evidence of some rebuilding but the Church seems to have been decommissioned later as there is evidence that the altar was demolished with some force! It appears to have been rebuilt for various uses including as a barn or store, as carbonized cereal grains were found on the higher layers inside the former Church. Further evidence of later “secular” use in the former “Nave” area include a collection of flint tools, an iron fish hook and a possible gaming counter as well as metalworking debris and nails. There was even evidence of burnt and twisted animal bone suggesting the burnt midden(rubbish tip). There was also debris which may be from the burning of the Church including 700 droplets of lead, from a possible melted roof fitting as well as three pieces of window glass ( one light green, two pale blue. By about 900AD however, the building along with the Burial Chapel was gone, as the area of the Glebe Field became a Viking Age market area, with the monastery most likely refocussed on the top of the Hill, where the later Whithorn Priory would be built in stone from around 1100AD.

In sum, the Northumbrian Church represents a fascinating and detailed example of an early Church building in Scotland and so far the earliest at Whithorn. It also fits into an emerging picture of Whithorn evolving from around 500AD into the Northumbrian period (around 650AD) as an important and monastic site with some accommodation between locals and incomers. The archaeology of the building itself just how much the use of the Glebe Field changed from around 700AD until around 900AD. It will be fascinating to see it brought back to life by the Whithorn Rebuild Project, hopefully in 2022.

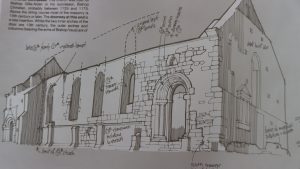

Blog 1: The Old Manse

This year, as the Whithorn ReBuild Project starts to train apprentices in traditional woodworking, it seems an apt time to reconsider the lost architecture of Whithorn. The ReBuild Project’s aim to “build” up to a reconstruction of the Northumbrian Anglo-Saxon Wooden Church. This church was found in the Glebe Field during the 1980s Dig at Whithorn and dated to 700AD. While this was the earliest direct archaeological evidence of Church buildings at Whithorn (the location of St Ninian’s Candida Casa, reputed to be built around 397AD, is still debated.), it wasn’t the last Church building found in that Dig.

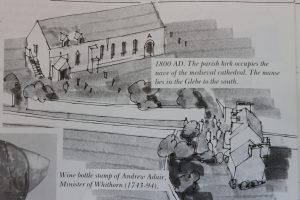

The last Church building in the area of the Glebe Field was the so called “Old Manse”, distinguished from the “New” Manse which was built in 1813AD, north of the Glebe Field and the modern St Ninians Priory Church. A Manse is the name for the home given to a minister or vicar along with their income in order carry out their role of administering their Church congregation.

The very existence of a Manse at Whithorn along with a single minister came about during the Scottish Reformation in 1560AD. Prior to this, while other parishes had a priest or vicar to do services in the local Church or Kirk, at Whithorn the evidence suggests that the local congregation took catholic services and mass in the Nave(entrance) of Whithorn Priory, which was also a Cathedral for a Bishop. When James IV of Scotland came on Pilgrimage in the early 1500s AD, reference is made to the “Outer” Kirk (Nave) and the “Rood” Altar, an Altar attached to the “Rood” Screen which divided the Nave from the rest of the Priory. It is most likely that a monk or priest would administer mass from this altar. The monks lived in communal accommodation in the area known as the cloister behind the Nave. They were part of a monastic order, the Premonstratensians, who were committed to living as a monastic community while ministering to the lay community of Whithorn. Indeed, the monastic community also provided the priests for many of the parish churches of the Machars. While there are late references to private quarters at the Priory in the 1500s AD, these were most likely were partitions of the Cloister accommodation.

The Manse appears to have started life in this period as the so-called “Commendator’s House. Built in the 1500s AD, it was the dwelling for a secular administrator called the “Commendator” who administered the Priory but did not otherwise participate in the monastic community. With the suppression and ruination of the Priory in the Scottish Reformation however, this building or a rebuild on the same site seems to become the manse of the Protestant ministers at Whithorn by the late seventeenth century. The “Nave”( the salvageable part of the Priory Complex) being rebuilt as a Protestant Cathedral between around 1605 and 1610, the monastic community was not replaced by Protestant “Canons” or Priests to administer the Cathedral as in the case for English Anglican Church, just a single minister. In the Scottish part of the “Glorious Revolution” of 1688, the Bishops were expelled from the Church (Kirk) of Scotland, leaving the Nave as a simple Parish Church with a minister. With the secure establishment of “Presbyterianism” in the Church of Scotland, Whithorn’s minister was just one of the many ministers in other Parish Churches in Scotland, the Church being run by Councils of these ministers and “Elders” (elected representatives from the Kirk (Church) Session of the individual parishes). Not even the “Presbytery” or regional church council met in Whithorn, instead having been held at Wigtown since 1588.

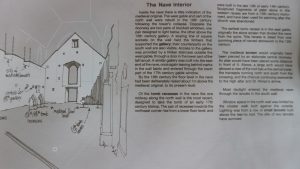

It is in the period after 1688 that we see glimpses of the life lead by the ministers of Whithorn and their manse. Despite Whithorn’s loss of status, there are hints of the ministers living quite comfortably. In 1691, the records for “Hearth” Tax, essentially a Tax on fireplaces, show that the Manse seems to be a large and grand enough building to have 3 fireplaces in it, likely meaning it was one of the bigger houses in Whithorn. A century later, in his description of Whithorn Parish for the first “National Statistical Account of Scotland” in 1795, Minister Isaac Davidson says that his manse was a …” good useful house”, which had a “glebe (land donated to the Church) of seven acres of very good land attached”. However in 1813, the succeeding ministers clearly had other ideas, as a new manse was built north of the current Church. It was only a few years later, possibly in tandem, that in 1822 that the Nave Church itself was abandoned and unroofed, as the new (and current) Protestant Church was built further up the hill as St Ninian’s Priory Church.

The Old Manse then appears to have been reused in various ways after 1822. It was used as a schoolmaster’s house before becoming a School and a soup kitchen, before becoming the house for a minister’s widow. When it was demolished seems not precisely known, but was certainly demolished by 1890-1, when a Market Garden was established by Gardener John Fairgrieve, in the Glebe Field with a greenhouse near the Old Manse area. The Market garden lasted until 1965, known for being unexpectedly fertile. Unfortunately the only visual evidence for the Manse before it was demolished, is found in a watercolour painting of Whithorn, undated but most probably painted in the early nineteenth century but after 1822, as St Ninian’s Priory Church as well as the “New” Manse are depicted, with the Old Manse as a large two storey building near to the ruined Nave.

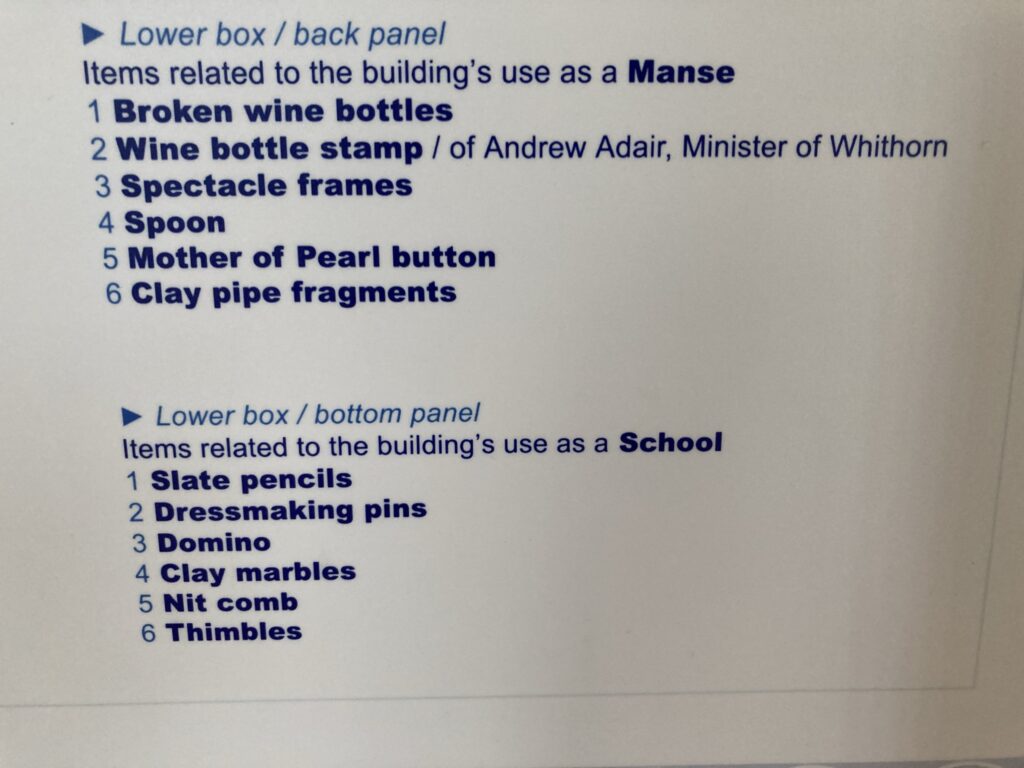

When the 1980s Dig excavated the Old Manse, they found evidence of early comfortable living for Whithorn’s Protestant ministers into the eighteenth century. For example, there was evidence of wine drinking, in the form of wine bottles as well as a wine bottle stamp with name of Andrew Adair, who we know was the incumbent minister until 1794. Evidence was also found of spectacles as well as broken eighteenth century china, a spoon and clay pipe fragments. However, evidence was also found for a possible reason for ministers moving to the new manse. The finding of drains and soakaways suggests the old manse was plagued with damp. This was most likely because, as the 1980s Dig found, the Manse had been unwittingly built over burial grounds and archaeology stretching back to 500AD! Intriguingly a fragment of a stone cross shaft believed to be “Anglian” (most likely dating to the Northumbrian period at Whithorn between circa 650-850AD) was recovered during the demolition of the Manse, possibly associated with the Northumbrian Church from 700AD.

There was also evidence associated the school established in the Manse after 1822. There was evidence of slate pencils as well as clay marbles, a domino and a nit comb. There was also evidence of sewing and dress making in the form of thimbles and hundreds of dress making pins which showed the former position of wooden floorboards. There was even evidence of the later more modern Greenhouse in the market garden from 1891. While it might seem ordinary to us, there were shards of broken flowerpots, greenhouse window glass and bottle fragments, as well as more intriguingly; coal ciders and an oil lamp wick. As it turned out, evidence showed that the Greenhouse not only had a planting bed and water tank but appears to have had been coal fired heating system at an unknown date. Could it have been in this Greenhouse that some of the prize-winning crops of strawberries and carrots that the Market Garden was known for, were produced until 1965?

The excavated area and records of the Old Manse allow us to see the development of the Old Manse from its origins in the sixteenth century through grand living of the late seventeenth- and eighteenth-century ministers and through reuse as a school, and then when demolished, the site of a Greenhouse of the early twentieth century Market Garden. It shows just how much can change even over periods that seem relatively modern to us. Also, especially in the case of the Greenhouse, it also shows the place that archaeology of the “modern” has as well as the older, more well-known remains at Whithorn.

Whithorn Trust Blog #30

November 2020

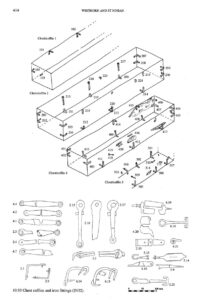

One of the most remarkable parts of the archaeology found at Whithorn, has been the burials from the early to late medieval period. In the “Glebe Field” at Whithorn, this is from as early as around 600AD to around 800AD with the “Early Christian” graves in the form of log burials and long cists. These types of burial were still being used when a newer but less common form of burial with chest coffins with fittings during the Anglo-Saxon Northumbrian period from around 640/650AD. There was then the burial of the mysterious “bundle of bones” around 900AD near the site of the Northumbrian burial Chapel. There was then a break in the use of the “Glebe Field” for burial, so the Viking Age Burial site is unknown. However, from around 1200-1450AD the Glebe Field was used again as a medieval graveyard for 2000 burials, possibly for the pilgrims visiting St Ninians Shrine at Whithorn Priory. There were also, however, during this period the richer graves of the Bishops of Whithorn, found on the Priory Hill dating to 1200-1400AD. This blog will not take in the graves in the “modern” Graveyard at the top of the Priory Hill, as those burials were put in after the Scottish Reformation in 1560AD, which many historians now view as ending the medieval period. However, our understanding of these burials is being transformed by new research such as from the Whithorn Cold Case Project which has shone new light on the earlier burials. .

The earliest burials at Whithorn, the “Early Christian Burials”, were found during the 1980s excavations at Whithorn, under head archaeologist Peter Hill in the “Glebe Field”. These burials were in a variety of forms. Possibly the most distinctive are the log coffin burials, with the individual interred within a hollowed-out log. While you might think that these would have been low status graves, it has been demonstrated by reconstructive archaeology done by the archaeologists that hollowing out a log takes a lot of effort and so it is most likely that at least some of these burials were for individuals with wealth and standing. There were also “long-cist” burials made up of stone slabs as well as what ap

pears to have been some burials with timber planks. One notable feature was a lack of grave goods, which archaeologists such as Adrian Maldonado see as resulting from local burial traditions that didn’t call for grave goods, rather than being evidence for a lack of resources on the part of the community. Peter Hill and his team had placed these earliest graves from the early sixth century AD( 500AD) around the time of the earliest evidence for a settlement at Whithorn, including the Latinus Stone , the earliest Christian monument in Scotland dated to 450AD.

However, one of the key findings of the Whithorn Cold Case Project was that the radiocarbon dating of the human remains showed the earliest dated remains in fact dated to around 600AD, showing them to most likely be a development later than 500AD. Possibly most distinctively, the radiocarbon dates show that these grave types, particularly the log burials, were being used right through the period and into the 700s and 800s AD at Whithorn. This suggests that there was a relatively stable comm

unity at Whithorn from around 600AD with these burial traditions, even when Whithorn came under the control of the Anglo-Saxon Kingdom of Northumbria (originating in what is now northern England) in around 650AD. This seems to complicate some previous notions among some archaeologists that changes in archaeology on a site during the period to around 1000AD must be the result of large numbers of new people bringing this new “material culture.” The isotope analysis done on the teeth or dentition of these human remains, show that most of the burials had a similar diet suggesting that apart from a few incomers, most of the burials were individuals born and raised locally. This was a mostly terrestrial diet, meaning not many fish were eaten, despite being only a few miles from the sea.

The next distinctive group of burials come from the Northumbrian Monastery found in the Glebe Field in the 1980s, which was dated to around 700AD. Beside the substantial wooden Church and across from the feasting halls was found a burial chapel. This burial Chapel, which was made of clay with stained glass windows, had four burials inside. These burials were found within chest coffins, two of which had extensive iron fittings including key mechanisms. Study of the remains have found that the burials are of two men and two women dating to the 700s AD, with isotope analysis showing one of the individuals could be from north eastern England. It has therefore been argued that at least one of the burial chapel individuals may have been from an elite group coming into Whithorn during the Northumbrian period. The possibility has been mooted that there could be nuns and monks, with the argument that this is evidence for a “Mixed” Monastery. This would be like Monasteries such as Whitby during this period, where monks and nuns would live in different areas on site but worship together; but, counter to this, there is no segregation of the burials.

In addition, the area in front of the burial chapel had a remarkable survival: a Children’s burial ground. It is remarkable given that evidence of human remains from children is rare. Indeed, despite the evidence of fifty-five burials, the survival of bone on site was limited. However, some bone from one burial was dated to the 700s AD, confirming it to be of the Northumbrian period. While the existence of such a graveyard is saddening, on the other hand it does show care and consideration for the burial of infants during the period.

However, the most mysterious burials found in the Glebe Field, during the 1980s Dig, were the enigmatic “Bundle of Bones.” The “Bundle of Bones” is so named because it was found in the ground as a grouping of disarticulated cremated bone from several individuals near the burial chapel. Thought to date to around 900AD it was initially thought to be evidence of “pagan” burials and linked with the evidence of a large fire in the area of the burial chapel and wooden Church in around 840AD, as evidence for Viking incursion and destruction. Indeed, this seemed to match with a change in the area of the Glebe Field, from a monastic precinct to a large market area with evidence for trade goods and craft manufacturing. However, with a recent re-evaluation of the evidence, it is now argued that while this settlement can be termed “Viking Age” , it is not a “new” settlement built on the ashes of the old but an evolution of the Northumbrian settlement. For example, there is the evidence that runic inscriptions from the “Whithorn School” Monuments dated between 800-1000AD are Anglo-Saxon, not Norse. In addition, the large fire was found not to have extended from the area of the wooden church into the rest of the settlement. Therefore, while the “Bundle of bones” has been radiocarbon-dated to around 900AD, it has been argued by Dr. Maldonado not to have been a “Pagan” burial but a re-burial of human remains damaged by the aforementioned fire in a deliberate re-location near the site of the burial chapel. It has been argued that the area of the monastery and St Ninian’s Shrine most likely refocussed onto the Priory Hill during this period.

What is clear however, is that there was a break in the use of the area of the Glebe Field for burial. We do not know where the cemetery or graveyard for Viking Age Whithorn was located. It appears that burial stops after the change of the area of the Glebe Field into the Viking Age marketplace. This is however most probably because such a cemetery was sited outside of the area of the Glebe Field. This means it most likely it is under the modern houses, gardens and streets of modern Whithorn.

It appears to have only been much later, in around 1200AD, that the area of the Glebe Field was reused for burial. The 1980s excavations found evidence for a large late “Medieval” Graveyard in the Glebe Field with two thousand burials excavated dating to between 1200-1450AD, though there was possibly another two thousand burials ( for a total of 4000) that were not fully excavated. This was a huge number of burials for the relatively small area of the Glebe Field, so even though they appear to have been buried in rows, the sheer number of burials has led to the individual graves being disturbed by adjacent graves. However, what might seem most surprising is that these graves were amongst the simplest graves found in the Glebe Field. The graves seem to have had no evidence of any coffins of any kind. All there was apart from the human remains was evidence of bronze pins and fittings, suggesting that the individuals had been buried in shrouds, but nothing more than that. This may imply that these individuals may be relatively poor, but this is by no means certain. There has been some debate as to the identity of the individuals buried in this graveyard. While it is possible that some may be local to Whithorn, the placing of this graveyard, just downhill of where the Whithorn Priory Cathedral stood, has led to the argument that many could have been pilgrims who came to St Ninian’s Shrine at the Priory Cathedral to obtain the aid of Whithorn’s Saint. St Ninian was believed to help pilgrims in many forms, for example in the curing of skin diseases such as leprosy. This may explain the pilgrimage of King Robert the Bruce to Whithorn in the last year of his life in 1329AD. These burials are yet to be tested with up-to-date radiocarbon dating and isotope analysis so it will be very exciting when this happens, as isotope analysis in particular would help us in finding out where these individuals came from and therefore whether they are likely to have been pilgrims.

This leads us to the group of burials dating to the same period as the late “Medieval” graveyard but are sited elsewhere. The Bishop’s Burials were found not in the Glebe Field but up on the Priory Hill in the late 1950s and 60s. Found by accident above the Crypts of the Priory (where the shrine of St Ninian was situated), the resulting excavations, led by inspector of Ancient Monuments, Roy Ritchie, uncovered one of the best examples of high status clerical burials in Scotland. Some thirty high-status graves were found with rich grave goods and carved and shaped sarcophagi. It was identified that these were high status clerics and nobility who had the honour of being buried at the site of the High Altar of the Priory Cathedral and of being buried above and near the Tomb of St Ninian, below in the Crypts. Isotope analysis showed that the individuals identified as Bishops had a large amount of fish in their diet (certain Holy days precluded consumption of red meat) and were identified as most likely coming from the area of southern Scotland or northern England. Through further radiocarbon dating, individuals among them could be named by being cross referenced with documents. The Bishops of Whithorn identified included Bishop Walter(died 1235AD), Gilbert(died 1253AD), Henry(died 1293AD and buried with the ornate “Whithorn Crozier” dated to 1175AD) as well as Michael(died 1359AD) and Thomas(died 1362AD). There were other individuals, some who may have been other high status clerics, but some may have been high status nobility, who had enough influence to buried at the High Altar, in the hopes of an easier journey to heaven.

Therefore, in this whistle-stop tour of burial in medieval Whithorn, we can appreciate the sheer length of time during which burial has taken place at Whithorn. It is also not as straightforward as some might think. It is not the case that burial rites necessarily went from less elaborate to more elaborate over time. As hinted at, hollowing out a log for a Log burial in around 600AD was probably as time consuming, if not more so, than wrapping an individual in a shroud with a bronze fastening. Difference in status may have something to do with that, but we must be careful when identifying relative differences in status. Grave goods can show great social status in burial traditions that call for them, but not all burial traditions do so. We should be careful, when comparing the status of the 600/700s AD log and long Cist burials against the late medieval Bishops burials for example. In summation, Whithorn’s medieval burials are a cornerstone of our understanding of Whithorn’s medieval history. With the ongoing research by the Whithorn Cold Case Project, including the possibilities for DNA testing of some of the human remains, there is still so much more they can tell us in the future.

Whithorn Trust Blog #29 2020

Was early medieval Whithorn a School for Irish Saints? Early medieval Whithorn and Ireland

Situated in the Machars Peninsula, facing the Irish Sea, it is not surprising that Whithorn has connections to Ireland. There were many connections that Whithorn had to Ireland within the early medieval period in particular. These range from possibly as far back as around 600AD through to around 1000AD. One of the most intriguing connections is the claim that Whithorn was a School for Irish “Saints” from the seventh century AD. There is even the argument that one of the scholars at the Monastery School, Finnian/Finian of Moville, was possibly the historical St Ninian himself. Was there such a School and what does it tell us about the early medieval origins of Whithorn?

Firstly however, we must look at who this “Finnian” was. Historians like Fiona Edmonds and Thomas Clancy have discussed the possibility that Finnian may have been the historical figure who became known as St Ninian. This is because, despite the traditions surrounding St Ninian, who is believed to have active at Whithorn in around 400AD, no contemporaneous sources from the period mention him. St Finnian (circa 495-589AD) was a monk and bishop associated with the Monastery of Moville  in County Down Northern Ireland. As a boy, he is claimed in the “Life of Finanus(Finnian)” to have been taken by a Bishop “Nennio”( another candidate for Ninian) to study at a monastery famous for scholarship known as the “Magnum Monasterium”, thought by scholars to be a monastery, at “Futerna” the Irish rendering of Whithorn itself. Like St Ninian, Finnian was not born in Ireland but was described as a “Briton”, a term then used for someone from the island of Britain who spoke a “Brythonic” language like Old Welsh – “Cumbric.” Indeed, Kilwinning in Ayrshire has been claimed as a burial place of St Finnian, but some historians like Edmonds see this as an attempt by the monks of Kilwinning to claim St Finnian from Moville. They are also both “high born” in being from noble or royal lineage. There are even some shared “miracles” that both Saints performed. For example, both are claimed to have cured the miraculous blindness of kings who had either banished or attempted to shun them. They also both make journeys to Rome. St Finnian would go on to be the teacher to another important Saint in what is now Scotland, St Columba, who would establish the monastery of Iona in 565AD. Historians like Thomas Clancy have therefore argued that St Ninian was therefore one and the same with Finnian of Moville. There is also evidence from lists of Saints Names in Ireland, known as “Martyrologies”, that Ninian is known in the Martyrology of Tallaght, composed between 828-833AD.

in County Down Northern Ireland. As a boy, he is claimed in the “Life of Finanus(Finnian)” to have been taken by a Bishop “Nennio”( another candidate for Ninian) to study at a monastery famous for scholarship known as the “Magnum Monasterium”, thought by scholars to be a monastery, at “Futerna” the Irish rendering of Whithorn itself. Like St Ninian, Finnian was not born in Ireland but was described as a “Briton”, a term then used for someone from the island of Britain who spoke a “Brythonic” language like Old Welsh – “Cumbric.” Indeed, Kilwinning in Ayrshire has been claimed as a burial place of St Finnian, but some historians like Edmonds see this as an attempt by the monks of Kilwinning to claim St Finnian from Moville. They are also both “high born” in being from noble or royal lineage. There are even some shared “miracles” that both Saints performed. For example, both are claimed to have cured the miraculous blindness of kings who had either banished or attempted to shun them. They also both make journeys to Rome. St Finnian would go on to be the teacher to another important Saint in what is now Scotland, St Columba, who would establish the monastery of Iona in 565AD. Historians like Thomas Clancy have therefore argued that St Ninian was therefore one and the same with Finnian of Moville. There is also evidence from lists of Saints Names in Ireland, known as “Martyrologies”, that Ninian is known in the Martyrology of Tallaght, composed between 828-833AD.

However, what of the “Magnum Monasterium”, what is the evidence for it at Whithorn? In terms of the archaeology, the main physical evidence for a monastery dates to around 730AD, in the form of a large wooden Church with a burial chapel (with stained glass windows) and feasting halls. The evidence for the earliest settlement at Whithorn from around 500AD, suggests a more secular elite settlement with evidence for imported pottery and glass for vessels from the Mediterranean. This was all found in the 1980s Dig in the “Glebe Field” at Whithorn. As Fiona Edmonds argues, the conception of Whithorn as having a monastic school in the seventh century AD does have some backing from sources such as “The Miracles of the Bishop Ninian.” This long poem, written possibly around 715AD most likely by a monk in the Anglo-Saxon Northumbrian Monastery at Whithorn (the Northumbrians had conquered the area in around 650AD). It makes the statement that St Ninian was a “teacher famous in the world.” While this is hagiography, it does seem to show the tantalising possibility that this reputation for teaching by Ninian may have had a legacy of a “teaching” monastery at Whithorn older than around 700AD. Indeed, as Edmonds points out, a letter surviving from St Boniface to Pehthelm the first Northumbrian Bishop of Whithorn seeking advice on a question of Canon Law suggests that there was a substantial library at Whithorn between 731-735AD when Pehthelm died in office. While this library could just date from the Northumbrian Monastery, could it be a continuation of an earlier iteration of the monastery in the 600s AD? There is also the point to be made, that the earlier part of the settlement from 500AD onwards appears to have been inside an oval shaped enclosure, which does fit with early Irish monastic enclosures.

There has been some new analysis (Cold Case Whithorn) of the early Christian burials found at Whithorn in the 1980s Dig. The radiocarbon dating for these burials shows that the earliest burials date from around 600AD and continue through to around 800/900AD. As Adrian Maldonado notes, these burials do not seem to originate at the earliest period at Whithorn around 500AD as was previously thought; they appear to start later. There is also the matter of the burials being a mix of males and females, rather than being predominately men. Could this be evidence of the cemetery being for a potentially “mixed” or double monastery(of monks and nuns living separately but worshipping together) of the seventh century AD, before the Northumbrian period, which could have been the “Magnum Monasterium” of Irish sources?

There are however reasons for caution. Previously there had been the argument that the type of burial known as a “Log coffin” burial found in the early cemetery, was an introduction by Irish Monks. However, log burials date from the earliest circa 600AD date and are used through to around 800AD. This seems to show log burials as already being at Whithorn as a form of burial. Furthermore, what has also been surprising, is that isotope analysis on the burials looking for diet and indicators of origin, showed no current indications of incomers from the west including Ireland during the period of the cemetery. This does not preclude possible interaction but it is strange to find no evidence of burial of individuals yet who originated in Ireland during the period.

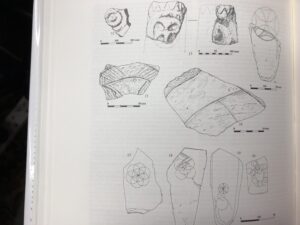

This is not to say however, that this was the only period of Irish influence at Whithorn. There were several stone sculpture fragments with cross designs found in the 1980s Dig at Whithorn, as well as some in Whithorn Priory Museum that date to the Northumbrian period at Whithorn. The predominant “compass drawn” designs in particular show evidence of Irish connections, for example with similar designs at Gallen Priory in County Offaly in southern central Ireland. There was considerable Irish influence in the Anglo-Saxon World but especially Northumbria. Most famously the monastery of Lindisfarne in north east England was founded by St Aidan from Iona. Pertaining to Whithorn, Pehthelm Bishop of Whithorn mentioned earlier had previously studied at the monastery of Malmesbury founded by the Irish monk Maildubh in south west England. Indeed, it has therefore been argued that with the interaction between Irish monasticism and “Roman Catholic” monasticism at that monastery, Pehthelm may have been sought out for appointment as Bishop of Whithorn as a mediator between the two traditions. This would be especially so if he were taking over an existing monastery at Whithorn with links to Ireland from the 600s AD.

There was also interaction between Whithorn and Ireland later into the Viking Age. The excavations at Whithorn in the 1980s found that the area of the Glebe Field showed evidence of a change in the site from around 840AD, where the monastic character of the wooden church and burial chapel was replaced by a Viking Age marketplace. There was evidence of trade and craft including not just merchants’ weights with evidence of leatherworking and comb-making but pins as well. The Thistle headed pins were distinctive in being like pins found in Viking Age Dublin. While Dublin was at the time a Viking settlement, the population had mixed with the Gaelic Irish so that there was a mixed Viking-Gaelic culture. They are therefore often called “Hiberno-Norse.” While it is now argued that instead of supplanting the previous population at Whithorn these Hiberno-Norse became part of a polyglot settlement, this helps place Whithorn in a vast trading network in the Irish Sea area and beyond. This both shows links to Ireland but also links to Norse world including the Western Isles and further.

Therefore, Whithorn had a wide array of connections with Ireland during the early medieval period. Even if the late sixth/seventh century AD connections in terms of a monastic “School for Saints”, is still being debated there is enough evidence to suggest some interactions with Ireland. This then extends into the Anglo-Saxon Northumbrian period with considerable Irish influence on the surviving sculpture at Whithorn and into the Viking Age with links to trade with Dublin and the Irish Sea area.

Whithorn Trust Blog #28 2020

Weaving and spinning in Medieval Whithorn

One of the most fascinating ways we can have a glimpse of medieval life, is through the evidence for the making of textiles and clothing. This was a period where such production was small scale with many small producers. For many people, their clothes would have been made in the family home. There was a whole series of processes and tools involved in making textile and clothing, not just in the weaving of the cloth but also the prior process of spinning, processing the fibres of wool and linen and combining them into yarns before weaving. There was also the matter of fitting the clothes together, which was achieved, not just with brooches, buckles and belts but also pins that would literally pin clothes together.

One of the first processes, before the weaving could commence was spinning. Spinning is the process where the raw fibre of the wool or linen from flax could be twisted, drawn and straightened into processed fibre. The fibres would then be spun together to make strands which then be combined into thread or yarn. This would have been done with what was called a distaff and spindle. The distaff is a staff or baton that holds the raw fibre, feeds it to the spindle and prevents it from tangling. The spindle is a stick to which the fibres are attached at the other end, with a weight known as a “whorl”(which normally has a hole in the middle for the stick) that helps the spinning of the fibres. Sadly, there appears to have been no distaffs found at Whithorn, being most likely made of wood, reducing the chances of survival in the ground. The wooden parts of the spindles do not seem to have survived either but some of the spindle “whorls” have. Indeed, there were ninety-three of them found onsite at Whithorn. These were found in the earliest archaeological layers at around 500AD through to 1600AD and beyond. The greatest number come from the layers from 1000AD to around 1600AD. While the majority appear to be made of stone, either “greywacke” or sandstone though two were made of shale, a smaller number were made from bone. Some others were made of lead. The Spinning Wheel, which was introduced to Europe in around 1400AD was an early “mechanisation” of the process, with the action of the wheel replacing the weight provided by the spindle whorl. However, there was no such evidence of spinning wheel parts from the excavations, most probably because of the wheels most probably being made of perishable materials like wood. However, the large number of stone and lead spindle whorls dating to the layers from 1300AD, suggest a continuance of traditional spinning techniques. Just how traditional spindle whorls and distaffs were, can be shown by the two spindle whorls found in Iron Age Roundhouses found at the Black Loch of Myrton five miles west of Whithorn. The earliest Black Loch Roundhouses date to 450BC.

After this, the thread from this spinning process was put on a Loom for the process of weaving the textiles and clothing. It appears that from the evidence from the 1980s Dig at Whithorn, the most likely Loom used at Whithorn through the medieval period was the “Warped” or Vertical Loom. The Loom was an upright frame made normally of wood, with two side “bar” planks with a bottom bar and top bar. The yarn would be hung or “warped” lengthwise from the top of the frame and held down by weights known as “Loom weights” to keep them taut. The transverse or horizontal yarns known as the weft, would then be inserted under and over the “Warped” threads, weaving and making the cloth. This could have been done by hand but also by use of a “shuttle” a holder for the weft as it was woven through the warped threads.

In the 1980s Dig, twelve stone objects were identified at “loom weights”. Seemingly almost half of them came the earliest layers of the excavations, between 500-700AD. Three were tentatively dated to the 1250-1600AD, though it was argued that, given the evidence of disturbance by graves from the 1200-1400AD period, these weights could have come from the earlier 700-840AD layer beneath. Two however came from better dated 1250-1400AD context. Most looked like large discs of greywacke or sandstone with drilled holes in the middle, which would have held down the warped thread. What was strange and pointed out by the Dumfries and Galloway Council Archaeologist Andy Nicolson, was that there seemed to be no such weights in the 1000-1250AD layers of the excavation, in which a great many spindle whorls for spinning had been found.

There was also the survival of what have been argued to be weaving implements on site. Five tools made of bone appear to be pointed tools for weaving. Two of them appear to date to the 1000-1250AD period and these were tools that most likely were used for either lifting warp threads or for “beating up” or pushing the weft threads together. It appears that these slender bone tools may have had much the similar role to a weaving comb.

Rather remarkably, textile, some of which appears to have been associated with clothing, survived in the ground in the Glebe Field. While these survived only as fragments, they give a hint at the textiles and clothing on site in the medieval period. The earliest textile was a length of “Z-Spun” mid brown woollen thread found in a waterlogged part of the site dating between around 840-1000AD. The waterlogged nature of that part of the site may have helped preserve this textile. There were six fragments associated with the medieval graveyard, dating to between 1200-1400AD. These included five fragments of woollen “twill” (a diagonally patterned weave like modern denim) that were grey-brown in colour. One of these fragments was found attached to the shank pin of a brooch. This brooch is an “Annular” Brooch is thought to date to the thirteenth century AD. There were also three fragments of woollen tabby (simple checkerboard weave) which was of an indeterminate date. Another woollen tabby fragment was attached to a brooch or buckle.

This brings us on to the objects that people used to attach the various parts of their clothing together. Throughout the early to late medieval period, in addition to using belts, buckles and brooches as you might expect, there were also lots of objects like pins that were found at Whithorn during the 1980s Dig. During the medieval period, clothing was most often literally pinned in place. Made of copper alloy, there are various types of pin found in the 1980s Dig at Whithorn. Right through from long pins, the earliest of which date from the sixth century AD, this seems to develop into the stick pins which date to the Viking Age period at Whithorn of around 840-1000AD( some of which had a “thistle” head). There appears to have then been the appearance of so called “Ring pins” ( with a copper loop at the top) which come from the area of the 1200-1400AD Medieval Graveyard but which may have been displaced from an earlier 1000-1200AD layer. This is in addition to copper alloy buckles. There are for example two buckles from the layers dating to around 700AD through to two buckles with decorated belt plates dating to between 800-1000AD. There are also two buckles with two belt loops and two belt pins which seem to date to the 1300-1400s AD and were associated with the medieval graveyard. Most interestingly there are also copper alloy “hexafoil” flower studs found in the area of the Medieval graveyard which most likely came from a late 1400/1500s AD belt. Several of the earliest copper brooches appear to date to from the 1300-1600AD period. There was also surviving leather belt and strap ends that may date to the same general period. While it is possible the later medieval objects may have been from pilgrims buried in the medieval graveyard, from outside of Whithorn, at least some were most probably from local people.

Therefore, we have a glimpse of how clothing and textiles were made and put together in medieval Whithorn. We have the evidence for the means of spinning the raw wool and linen before the weaving took place with the spindle whorls. Then we have the evidence for the loom weights that held down the yarn on vertical looms while the warped yarn and the weft yarn were woven together, possible with the weaving implements that have been found. We have precious fragments of textile showing woven wool. Lastly, we have the pins, brooches, buckles and leather belts to show how they put on and wore their clothes. It therefore gives a tantalising glimpse of the lives of ordinary people, whether townsfolk of Whithorn or pilgrims during the medieval period.

Whithorn Trust Blog 27 2020

Games and Music in Medieval Whithorn

It might be thought that the medieval period at Whithorn and elsewhere for that matter was a hard time to be in. That is probably true. Most people were subsistence farmers, living off the land and even the people in early and late medieval towns like Whithorn often had to grow some of their own food as well as make and trade goods like cloth to sell. With famine a very real prospect as well as diseases and ailments that are treatable today but could kill then, life was certainly harder than in modern Scotland. However, this does not mean that people in the past had no outlets in their lives. As found at Whithorn, there is evidence that people after a hard day’s work in the fields or in a workshop, did have some free time to relax, play music and play games. Obviously for the elites of Whithorn, the merchant burgesses, visiting nobility and even some of the monks, there was more time for this sort of leisure.

The evidence of playing games, particularly board games at Whithorn, comes from the 1980s Dig in the “Glebe Field” lead by Peter Hill, just south of the ruins of Whithorn Priory. The Dig found a wealth of archaeology from the 5th century AD right through the medieval period and even some remains from the eighteenth and nineteenth century. Our evidence for gaming comes from the period from around 1000AD. Three stones were recovered from the excavations with incised gaming boards on them.

Two of the Stones, due to the archaeological context (defined place or area of an excavation) that they were found in, are thought to have been deposited sometime in the later twelfth century AD. It appears that these were thrown away, as one was found in the southern sector of the Dig in a rubble bank and the other was found in the drain near the remains of a building most likely dated between 1000-1200AD. One had boards incised on both sides of the Stone. The other was incised on only one side. The archaeologists have argued that the gaming grids on these stones appear to most likely be for a game called “Merels” otherwise known “Nine Men’s Morris.” This is a game whose origins may go back to Ancient Rome and even as far back as Ancient Egypt. The game has been claimed to be a more “Adult” version of Tic-tac-toe, where the object of the game is for two players to use their gaming pieces to make rows of three with their pieces, called “Mills”. This allowed that player to claim one of the other player’s pieces. The aim was to reduce the opposing player to two pieces, preventing them from making rows. This game was popular in the medieval period. It appears to have been widely popular throughout medieval society and that does include monasteries. There are incised merels boards found on stonework at Arbroath Abbey and Dryburgh Abbey possibly both dating to the thirteenth century AD. Dryburgh’s example was found on a ruined wall of the Nave while the example from Arbroath Abbey is on a stone fragment reused in a post Reformation Wall. It has been argued that both examples are most likely the result of medieval masons working at the Abbeys, incising the Stones to play the game in rest periods. Could this have been the case at Whithorn as well? Some historians have argued that the East End of Whithorn Priory was extended around 1200AD. Could the merels Boards at Whithorn be evidence of Masons working on Whithorn Priory? However, it could be that the merels boards were made by ordinary people or even monks. There are merels boards found incised in the Cloister seats in many English Cathedrals, so even monks seem to have played it.

The third Stone with an incised gaming board, appears to have not been a merels board but 7 rows by 7 column board most likely used to play Tafl. Tafl is a family of board games also known as hnefatafl. One player has the “King” and a small number of pieces in the middle of the board. The opposing player has a greater number of pieces surrounding the “King” player. The opposing player had to try take the “King” piece, while the “King” player had to try get the king piece off the sides of the board. Hnefatafl is the Norse version of this game but there were also variations such as the Irish Brandubh. Interestingly the context from which the Tafl board came from suggests that this board was deposited within the area of the mid to late medieval Graveyard in the Glebe Field, where the burials date from around 1200AD and 1400AD. However, it has been argued by Andrew Nicolson, Dumfries and Galloway Council Archaeologist, that it could have been displaced from another similarly dated context/layer. So was this Tafl board buried with a Whithorn resident in a grave, or maybe it was buried with a pilgrim who had come to Whithorn. This would not be surprising, as literary evidence such as from the writings of fourteenth century AD English Poet and writer Geoffrey Chaucer, shows that Pilgrimages were not entirely solemn affairs, especially on the journey to Saint’s Shrines, with Pilgrims known to drink, dance and some most likely playing games like merels and Chess.

What was also found in the 1980s excavations were the possible gaming counters or pieces used on these gaming boards. There were some twenty-four stone “small discoids” between 12.1mm and 31.5mm in diameter. About a third of this total ranged from 22-24mm, which is significant because it was found that those discoids between 22-30mm would fit the gaming boards found onsite. It was also argued that the discoid with a cross on it, could have been the “King” piece in the Tafl Game. The gaming pieces were found in archaeological contexts on site which suggests a spread from around 1000AD through to the 1500/1600s AD. There is possible evidence of earlier game playing however with the additional finds of gaming pieces made from antler. It was argued that despite some of these antler pieces being in late medieval (1200-1600AD) contexts, the earliest ones were found in contexts dating to between 850-1000AD, suggesting that at least some date to the early part of the Viking Age settlement at Whithorn( roughly 800-1000AD), probably made from antler off-cuts from the antler workshops from around 800AD which produced the evidence of comb making on site. There were two other stone fragments with incised lines on them, which could represent earlier game boards, but which could not be confirmed, so these antler game pieces are the main indications of gaming earlier than 1000AD. While there was the possibility that some of the gaming pieces may have been dislodged from their original contexts by later layers of archaeology, it does seem that we have evidence for the playing of games and board games at Whithorn through the medieval period.